Haydon's first mural was painted at

Pickering College in 1934, and it was also his first commission

for public art. It would be approximately 20 years before the

next opportunity arose, but that occasion would begin a significant

new chapter in his career. Public art brought Haydon's beliefs

in community service, the artist's responsibility to communicate,

the importance of art in everyday life, and even his own religious

convictions to focus in one arena. In fact it was in the area

of religious art that he was most eloquent.

In an article Haydon wrote in 1965 for the International Journal of Religious

Education, he summarized his views on the artist's responsibility to communicate

effectively when working on religious art commissions:

"The artist is needed who will speak through

art to each particular congregation in a manner appropriate to it, so that

art will attract and not repel, lead

and not follow, inspire and not please. His qualifications are sympathy, sensitivity,

knowledge, and trust, in addition to qualifications as an artist. His task

is to make a work of art that has lasting meaning for the people who will live

with it. It will be good or bad not according to its style or place in contemporary

art, but according to its power and quality of expression, which also will

determine its right to survive."

He continues with:

"The burden of communication must be shared between artist and congregation

with leaders of the congregation having a key role interpreting the congregation

to the artist and the artist and the work of art to the congregation...sincere

religious art will speak directly, personally, and simply - being modern without

trying to be Modern, and seeking refined rather than extravagant means of expression."

Temple Beth Am, Chicago |

In 1956 Haydon began a long and fruitful association with Percival

Goodman, a New York architect known for Jewish temple designs.

Goodman had commissioned

artists such as Robert Motherwell and Adolph Gottlieb to create art works for

his previous temples. He also made a practice of asking that the people of

the congregation contribute some work toward the enhancement of their building

and left unfinished places in the building to be filled with works of contemporary

art. Now Goodman was looking for a Chicago artist to design an ark curtain,

a Parochet,

for his newly designed structure, Temple Beth Am, located at South Shore Drive

and Coles Avenue in Chicago. The congregation was specific about wanting

a Chicago area artist because their plan was to have the curtain done by the

women of the congregation in gross point tapestry. They needed an artist to

design and select colors for the work, as well as instruct and assist the women

in its execution. Only a local artist could devote enough time and attention

to a project of this scale. On Goodman's part, he was looking for an artist

who was good with abstraction but who would also incorporate symbolic content.

In seeking out a local artist, Goodman turned to the sculptor, Milton Horn.

Milton Horn had lived and worked in New York from 1922.

In 1939 he moved to Olivet, Michigan where he was the

Carnegie Professor of Art and Artist-in-Residence

at Olivet College until 1949, when he moved to Chicago. Horn's first commission

in the Chicago area was also his first commission for a synagogue.53 It

was a relief sculpture for the exterior of the West

Suburban Temple Har Zion in

River Forest, IL. Already a well known artist, Horn produced a sculpture

for this temple where "For

the first time, so far as is known, a human form appeared

on the exterior of a synagogue.

The sculpture was noticed around

the

world."

Horn and Haydon were acquainted not only from exhibiting together in various

group shows and working together on the Ferguson Fund issue in 1955, but also

from being on an Art Institute of Chicago advisory committee in 1952 that studied

how the Art Institute could help Chicago art achieve more prominence. The committee,

selected by Daniel Catton Rich, the museum's director and who appointed Haydon

as Chairman, came to be called the Haydon Committee on Chicago Art. (Box 322C(3))

By 1956 when Goodman was seeking a local artist for the Temple Beth Am Parochet,

Horn was well known to both Goodman and Haydon, so it was a natural step for

him to propose Haydon for the Parochet project. In his letter to Goodman, dated

8/12/56, Horn recommends Haydon, lists his qualifications and mentions Haydon's

father, A. Eustace Haydon, to demonstrate that Harold would be sympathetic

to religious subjects. Horn also notes that Harold has "a

good deal of tact, so that the women would do as he wishes." Estelle

Horn, Milton's wife, was also encouraging over the project. When she sent Haydon

a copy of

Milton's letter of recommendation, she also described Goodman as "the

most publicized synagogue architect in the world," as

well he was, his reputation being established since the late 1930s.

Temple Beth Am was dedicated in June of 1957 and actual work on the Parochet

began in July of 1957, but Haydon began working on designs in the fall

of 1956. He took them through a variety of transformations before settling

on

his final

plan and producing a scale model for the congregation's approval. For the

doors, Haydon chose a Pillar of Fire and a Pillar of Cloud to represent

how the Israelites

were led through the wilderness, which he suggested in the planes of color

across the doors. The triangular side panels contain abstractions of cherubim

holding the commandment tablets on one side and torah scrolls on the other.

Symbols of the twelve tribes of Israel and the seven branches of the Menorah

are also incorporated. Its colors were chosen to "harmonize with the

stained glass windows of the Temple."

Horn's suggestions to Haydon concerning the style and symbolism were that "...the

design of the curtain must be read from everywhere in the sanctuary," so

he recommended using "...a series of large, symbolic

forms and well defined color areas." This

advice Haydon followed for both visual and practical reasons. In the construction

process, the design would have to be enlarged

to a full size cartoon and transferred onto the cloth. A line drawing with

clearly indicated color areas would be best suited for this purpose. Most notable

in his design, though, is the absence of the binocular vision style. While

still committed to this technique in his personal work, the symbolic content

and sacred purpose of the Parochet precluded any effort to promote his own

art philosophy.

The work was done in the rug hooking technique and took forty women 1,200 hours,

spread out over the course of a year, to produce the nine-foot high by twenty

two-foot wide work. They used 720 skeins of heavy wool rug yarn in 34 colors,

some of which were specially dyed. Haydon selected a very strong warp cloth,

drew the design on the reverse side, and indicated the color code and pile

depth-of-stitch numbers, making sure that the process and materials would be

easy enough to work with and would allow groups to work together. According

to his own description of the process:

"Several persons could work at the

same time on each part, pushing the needles through from the back of the

warp

cloth, and working from the center

out to

the edges. No warp frame or hooking frame was needed, and the workers could

sit around tables, seeing the pattern grow under their hands and enjoying

the company of their fellow workers."

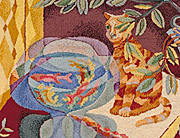

Cat and Goldfish Bowl |

After the women completed their

work, Haydon clipped and sheared some areas to sculpt the wool,

thus increasing the textural qualities as well as modulating

color areas. To understand the intricacies and subtleties of

the rug hooking

technique and how to apply it in an art context Haydon made rugs himself,

such as the one shown here, untitled (Cat

and Goldfish Bowl), to study the

process and what variations are possible, as well as to see the

color effects. Milton Horn had

advised him:"Remember that the gross

point surface receives light entirely different from paint. Each stitch

will not only catch a highlight

on it but

will also cast a shadow."

After the success of the Beth Am Parochet, Goodman asked Haydon to do a second

project for a new temple. It was to become, in Haydon's opinion, one of his

most important artistic productions. Never being one to shy away from a challenge,

his challenge now was to create two panels, each 8' x 5 1/2', in Byzantine

glass mosaic, although he had never worked in that

medium. The project was for Temple Beth-El in Gary, IN, where Goodman wanted

mosaic panels in the vestibule

to flank the entrance to the sanctuary.61 Subject matter for the Temple Beth-El

mosaics came as a suggestion from Goodman and was developed by Haydon with

the assistance of the temple's Rabbi, Irving Miller. Goodman's idea came from

the poet Hyam Byalik's work Law and Legend or Halakah and Aggada, and he asked

Haydon if he would accept the challenge of interpreting this poet's work in

visual form.

The Legend

(partial view) |

After a number of conferences with Rabbi Miller to discuss interpretations

and iconography, and correspondence with Goodman, Haydon arrived at a final

design that combines both traditional Jewish images with references to the

new temple's modern design, and even scenes of Gary, IN. Central to the panel

of The Law,

the figure of Aaron as high priest is cloaked in robes designed from the biblical

description found in Exodus. Interspersed in the panel are symbols of the twelve

tribes of Israel and other traditional references, as well as an I-beam to

represent Goodman's new steel and glass temple, while across the lower section

are scenes of Gary's steel sheds and smoke stacks. The other panel, The

Legend, recalls both the Tree of Life and the

seven branched menorah. Behind are the Pillar of Fire and the Pillar of Cloud,

which traditionally symbolize how the Israelites were led through the wilderness,

but are also, according to Haydon, a contemporary reference to the steel works

and smoke stacks of Gary. Along the lower portion of this panel there is an

image of the steel sheds, but more dominant is a scene of Lake Michigan's shore

with the sand dunes that are a prominent part of northern Indiana's landscape.

It took Haydon about three years to make both the mosaic panels, since he was

teaching full time during that period and only spending the summers working

on their fabrication. During the first eight months he spent time interpreting

Hyam Byalik's poetry, consulting with Rabbi Miller and selecting the iconography

from biblical and secular sources. By the end of May, 1958, Haydon had produced

his final drawings, along with a scale model of the vestibule. The summers

of 1958 and 1959 were spent at the Vermont farm constructing the first panel,

The Law. This panel was exhibited at the Renaissance Society at the U of C

from Oct. 18 - Nov. 14, 1959, before being dedicated in the temple on December

4, 1959. The second panel, The Legend, was completed by the fall of 1960, exhibited

at the Chicago Public Library, and was dedicated in the temple on November

25, 1960.

The type of mosaic construction Haydon used is extremely time consuming,

but it was a process he enjoyed and described in an article published in

the magazine

Inland Architect in 1965.62 The Byzantine glass mosaic technique uses tesserae

made by breaking glass disks into pieces measuring about 3/8" wide, 5/8" long,

and 1/4" to 3/8" thick. Each individual tessera is set in a fine,

slow drying cement with only about 1/16" left between each piece. What

defines the process as being in the true Byzantine technique is that the broken

edge of the glass is exposed as the mosaic's surface. Also, according to Haydon, "for

the richest color effects the mortar or mastic should be kept down an eighth

of an inch below the surface of closely spaced tesserae. Then the light entering

the interstices returns enriched in color, while the shadow lines of the interstices

serve as powerful means of drawing or modeling form."63 The broken glass

surface gives a shimmering, irregular face that plays more dramatically in

the light, unlike the smooth, flat surfaces found in ceramic or stone mosaics.

There are also seemingly unlimited colors of glass tesserae to choose from.

According to Haydon, "there may be as many as 10,000 colors available

to the mosaicist, plus thirty or more tones and hues of gold. Many of the glass

colors are shades and tints, for the more neutral tones are essential to color

modulation and are required to enhance the brilliance of pure hues."64

By doing these panels himself, Haydon was able to take advantage of such

an extensive array of colors and create a much more complex work than would

have

been possible if volunteers had done the tesserae setting. It also allowed

him to fully explore the medium and learn its advantages, subtleties and

limitations so that he would be able to teach others in the future.

His next Byzantine glass mosaic commission came in 1962-63

from the Church of St. Cletus in LaGrange, IL.

Their newly dedicated church had a St. Francis chapel that Father Gerald

J. Morrissey wanted to decorate with a mosaic. A very large project, the

mosaic

was designed to fit on three walls for a total of 45 feet in width. Its complex

design, showing different scenes from St. Francis' life, is organized into

irregular shapes of various heights. Congregation members did the actual

mosaic work, with Haydon instructing and supervising them along the way.

To coordinate

and control the quality of the work, the church organized an "All Parish

Mosaic Workshop" to train the 112 volunteers who participated in the

project. It took them only 3 months to lay an estimated 250,000 individual

tessera pieces,

approximately 500 pounds, in over 80 colors and 8 shades of gold.

Instead of using the direct method of mosaic construction that he used when

constructing The Legend and The Law panels, Haydon trained the congregation

in the indirect method, a method that was easier for the volunteers to follow

and that allowed the design to be divided among several workers. With the indirect

method, the design is worked in reverse and the tesserae are glued face down

to paper with a boiled flour paste. To begin, Haydon transferred the design,

in reverse and in full scale, onto large rolls of heavy paper, paper which

was designed not to warp or buckle when wet. He also marked each color area.

The design was then cut into sections and individuals or groups began the process

of gluing the tesserae. After the paste dried for 2-3 days, the work was transferred

to the wall, which had been prepared with a layer of a fine grained mosaic

cement. Following the design of the work, Haydon applied each papered section

to the wall, patting gently to embed the tesserae into the wet cement. The

paper was then wetted and removed from the face of the mosaic. Individual tessera

were checked and adjusted to assure each was well set. By carefully washing

the surface with a wet sponge, the remaining paste and cement on the tesserae

surfaces was removed. Once the cement had set for several days, a diluted wash

of water and hydrochloric acid was used to remove any final cement.

Some members of the St. Cletus congregation were hesitant about beginning

such an ambitious project, not certain that enough members would volunteer.

Father

Morrissey, though, had confidence and pressed forward, and of course Haydon

knew it could be done. Haydon did elect to do the 5 faces of St. Francis

himself, but he was counting on the inexperience of the volunteers to achieve

what he

called "a genuine primitive quality in the final result." It is

that immediacy and directness that give the mosaic a powerful and contemporary

look.

At the same time, that primitive quality, together with the shimmering glass

surface, give the work an other worldly aspect.

|